By Geeta Pandey and Suraj Karowa, Noida, Uttar Pradesh November 26, 2025

Parents hold up photographs of the missing children of Nithari

In the shadow of Delhi’s gleaming suburbs, the ghost of Nithari village refuses to fade.

Nearly two decades after the discovery of dismembered bodies near a affluent bungalow—earning it the grim moniker “India’s house of horrors”—the families of 19 missing women and children are grappling with a devastating twist.

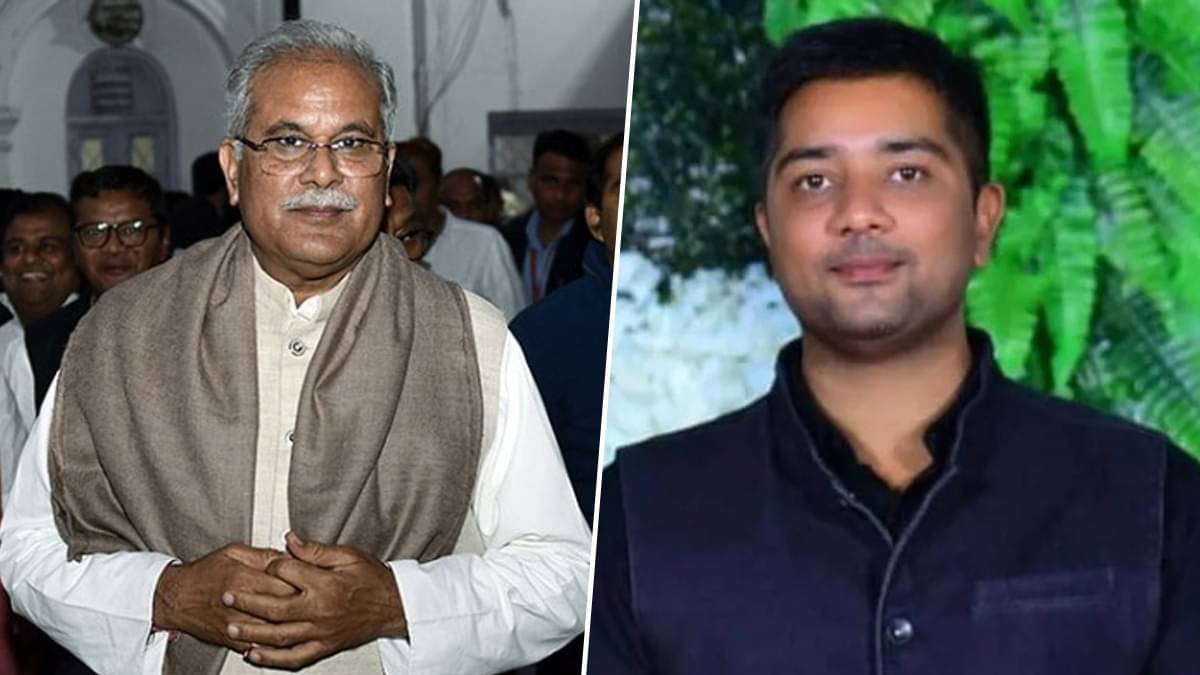

On November 12, 2025, India’s Supreme Court acquitted Surinder Koli, the last remaining convict in the case, citing a coerced confession and a botched investigation.

Surinder Koli walked free this month after the Supreme Court overturned his conviction

With his employer, Moninder Singh Pandher, already freed in 2023, the rulings have shattered any illusion of justice, leaving parents to echo a haunting refrain: “If they didn’t do it, then who killed our children?”

The Nithari killings erupted into national consciousness on December 29, 2006, when construction workers unearthed a sewer drain behind D-5 bungalow in Noida’s upscale Sector 31.

What followed was a macabre excavation: skulls, bones, and mutilated limbs of at least 19 victims, mostly young girls from nearby slums.

Jhabbu Lal Kanaujia and his wife Sunita want to know who killed their 10-year-old daughter

The horrors escalated with allegations of rape, cannibalism, and necrophilia, confessed by Koli, Pandher’s domestic help.

The affluent Pandher, a businessman often absent on work trips, and Koli, a poor migrant from Uttar Pradesh’s hills, were arrested amid public fury.

Protests rocked Delhi’s Jantar Mantar, with desperate parents waving faded photographs of their lost children.

The case laid bare India’s stark inequalities. Nithari’s victims hailed from impoverished migrant families in the adjacent slums—dalit laborers, vegetable sellers, and daily-wage earners lured by the promise of urban opportunity.

Pappu Lal says when Rachna, eight, disappeared in April 2006, police told him she had eloped with a lover

Their children vanished one by one between 2004 and 2006, dismissed by police as runaways or elopements.

“They said my eight-year-old Rachna had run off with a lover,” recalls Pappu Lal, whose daughter disappeared on April 10, 2006, after a short walk to her grandparents’ home, just two doors from D-5.

“I scoured cities and states for her. Eight months later, her clothes and slippers turned up in the lane behind that house.”

Jhabbu Lal Kanaujia’s story mirrors the agony. His 10-year-old daughter Jyoti vanished in the summer of 2005.

A former “press-wallah” who ironed clothes for Pandher’s neighbors, Kanaujia pleaded at the local station for 15 months.

Pappu Lal’s daughter Rachna’s remains were among those found near bungalow D5

“No closure—just a festering wound,” he says, voice cracking. On that frigid December day in 2006, he descended into the sewer himself, unearthing “skulls and limbs beyond the 19 cases that made headlines.”

DNA later confirmed Jyoti among them. Now 70, Kanaujia burned his case files in despair after Koli’s acquittal.

“I’m an old, broken man. Unless the guilty cops are jailed, there’s no justice.”

The Supreme Court’s 2025 order was scathing. Justices, acknowledging the “heinous offences” and “immeasurable suffering” of families, overturned Koli’s conviction in the final pending case—the 13th against him.

Earlier, he had been sentenced to death in multiple trials, but acquitted in 12. The court deemed his confession involuntary, recorded after 60 days in custody with a police investigator suspiciously present—”tutored,” they ruled.

Investigators, the bench charged, pursued the “easy course” by framing a “poor servant,” ignoring leads like organ trafficking flagged by a 2007 governmental committee.

Bodies showed surgical precision cuts, hinting at a darker network, yet probes stalled amid “negligence and delay.”

Pandher, acquitted across all cases by 2023 due to insufficient evidence, has proclaimed his innocence in interviews.

“I was framed,” he told media post-release. Koli, 55, emerged silently from Greater Noida’s Luksar Jail, vanishing from public view.

His lawyer, Yug Mohit Chaudhry, decried the CBI’s role: “All evidence was fabricated to shield powerful culprits.

Ask the CBI who the real monster is.” The federal agency, which took over after public outrage suspended six officers and transferred two seniors, has stonewalled BBC queries.

Uttar Pradesh police, too, offered no comment on the elopement dismissals or ignored complaints.

Nithari today is a fractured mosaic. The victims’ families have scattered—most fled the painful memories.

Kanaujia and wife Sunita remain, staring at Jyoti’s photo amid peeling walls. “God won’t forgive the killers,” Sunita weeps.

Pappu Lal tours the derelict sites: D-5, now a soot-scarred ruin sealed by bricks and overgrown bougainvillea, its yard choked with sludge.

“The stench lingers,” he says, pointing to the rear drain where Rachna’s remnants surfaced. Nearby, affluent homes gleam, a chasm underscoring the case’s social indictment.

Aruna Arora, 2006 president of the local Residents’ Welfare Association, laments the systemic rot.

“I begged senior cops and the district magistrate about vanishing kids from poor homes.

No one cared until bones surfaced.” Her words echo a broader critique: India’s justice system, plagued by delays and bias, favors the vulnerable least.

The Nithari probe, handed to CBI after riots, became a “botched” saga—tainted forensics, vanished witnesses, and whispers of political cover-ups.

For survivors, closure evaporates. Anupam Nagolia of Better World Foundation, who funded their legal battles, sees finality: “The Supreme Court is the end.

Now, only grief remains.” Yet Pappu Lal vows defiance. “I’ll file a fresh complaint, meet PM Modi and CM Yogi Adityanath.

Our children were India’s too—aren’t we owed truth?” Legal eagles like retired Justice Madan Lokur doubt reinvestigation’s viability: “Time has erased evidence; it’s impossible.”

As winter bites Nithari’s lanes, the air thickens with unresolved rage. The “house of horrors” stands as a derelict testament—not just to lost innocence, but to a justice system that acquitted the accused while condemning the innocent to eternal limbo.

Who killed the children? The question hangs, unanswered, fueling a cry that demands resurrection.

In a nation of 1.4 billion, Nithari whispers: without accountability, every child is at risk.

Discover more from AMERICA NEWS WORLD

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a Reply