By Suraj Karowa /ANW

London, January 3, 2026 –

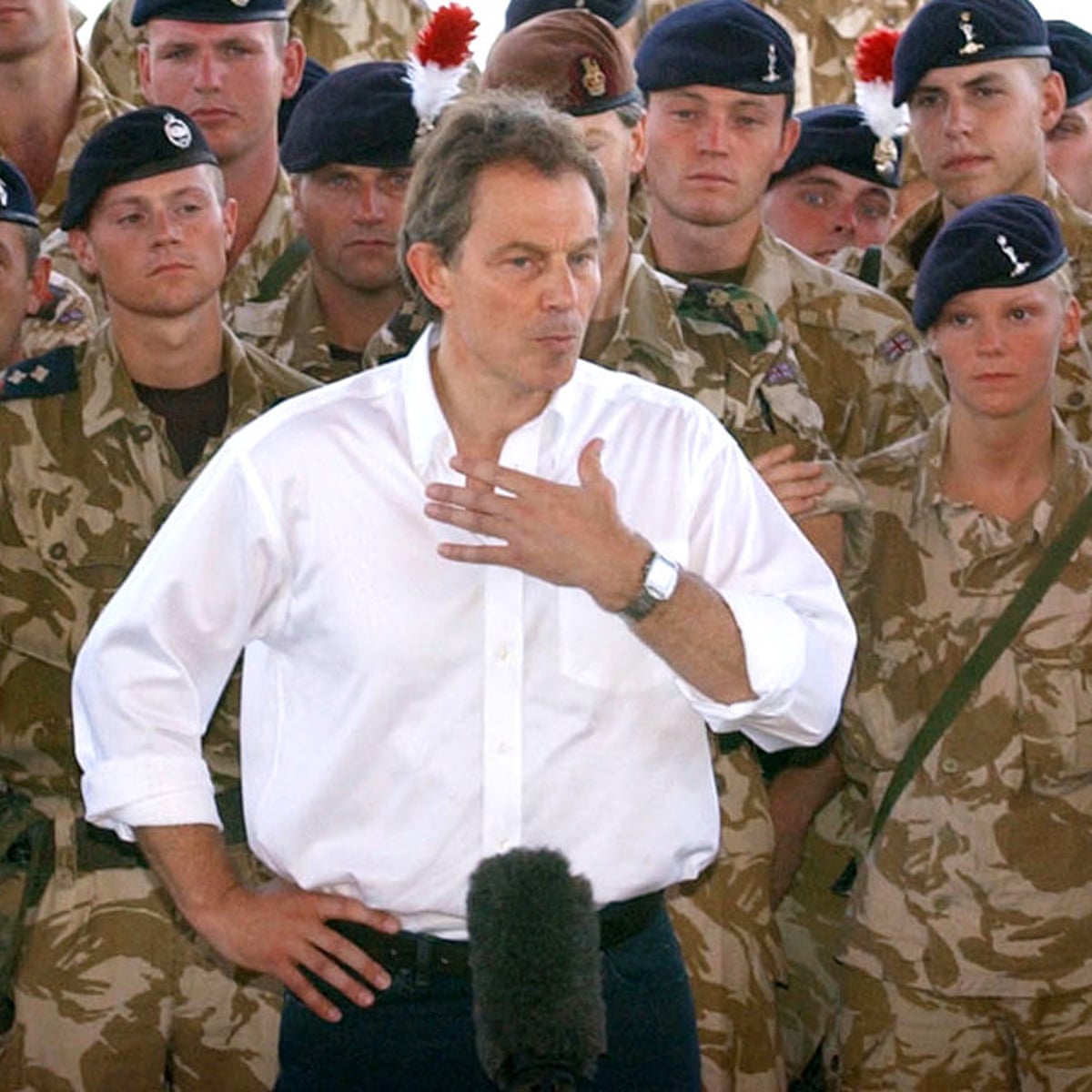

The UK’s Prime Minister Tony Blair meets British troops in the port of Umm Qasr in southern Iraq .

Newly released UK government documents have thrust former Prime Minister Tony Blair’s legacy back into the harsh glare of scrutiny, exposing his apparent efforts to insulate British soldiers from civil court trials over alleged abuses during the Iraq War.

The files, declassified on December 30, 2025, and now housed at the National Archives in Kew, paint a picture of a leader deeply invested in protecting the military’s image amid mounting domestic and international backlash against the 2003 invasion.

The 600-plus documents, mandated for release under the UK’s Public Records Act 1958 after 20 years, cover Blair’s administration from 2004 to 2005.

They span domestic policies on devolution to Wales and Scotland, but it’s the foreign affairs section—particularly Iraq—that has ignited controversy.

According to reports from UK outlets like The Guardian and BBC, Blair explicitly urged his private secretary for foreign affairs, Antony Phillipson, in a July 2005 memo, to ensure that accused soldiers faced only military courts, not civilian ones or the International Criminal Court (ICC).

United Kingdom Prime Minister Tony Blair addresses troops in Basra, Iraq, in 2003.

“It is essential that we are in a position where the ICC is not involved and neither is the CPS [Crown Prosecution Service],” Blair wrote, following a briefing on the brutal death of Baha Mousa, an Iraqi hotel receptionist beaten to death by British troops in Basra in September 2003.

Mousa endured 93 separate assaults while in custody, a case that became emblematic of systemic mistreatment.

Phillipson’s note to Blair referenced a meeting with then-Attorney General Lord Goldsmith and two ex-military chiefs.

It flagged the possibility of civil proceedings if deemed more appropriate, but Blair shot it down: “It must not.”

The directive came amid fears that high-profile civilian trials could erode public support for the war, already fraying over debunked claims of Iraqi weapons of mass destruction (WMDs).

Protesters against the war in Iraq gather outside the Houses of Parliament in London, UK, in January 2003.

Christopher Featherstone, an associate lecturer in politics at the University of York and author of The Road to War in Iraq: Comparative Foreign Policy Analysis, described Blair’s stance to Al Jazeera as a calculated bid for “military justice,” perceived as less severe and damaging to troop morale.

“Blair didn’t want prosecution through international law… he saw this as less punitive,” Featherstone said.

“He was very concerned about potential prosecution for UK soldiers as this would only amplify opposition to the war, at home and abroad.”

The Iraq War, launched on March 20, 2003, by a US-led coalition with staunch UK backing, remains one of Britain’s most divisive foreign policy chapters.

Blair justified the invasion as a moral and strategic imperative to disarm Saddam Hussein’s regime and free Iraqis from tyranny.

Yet, the Chilcot Inquiry in 2016 branded the intelligence on WMDs “flawed” and found no imminent threat from Saddam.

The conflict, which dragged on until 2011, claimed over 200,000 Iraqi civilian lives, 179 British troops, and more than 4,400 US soldiers.

Blair’s personal stake was profound. In a 2016 post-Chilcot press conference, he called the invasion his “hardest decision,” apologizing to bereaved families while insisting the world was “better without Saddam Hussein.” But the declassified files underscore his proactive shielding of the military.

In June 2002, even before the ICC’s Rome Statute fully activated, Blair penned a reassuring letter to Australian Prime Minister John Howard, downplaying fears of the court’s overreach.

“Responsible democratic states, where the rule of law is respected, have nothing to fear from the ICC,” he wrote, emphasizing it targeted only “failed states” or collapsed judicial systems.

This confidence proved prescient yet contentious. The ICC launched a preliminary examination into UK actions in Iraq in 2005 but shelved it in 2006 for jurisdictional reasons.

It reopened in 2014 after NGOs like Human Rights Watch and the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR) submitted dossiers on “systematic” abuses: beatings, sensory deprivation, sexual humiliation, and torture affecting hundreds of detainees.

Then-Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda’s 2020 report acknowledged a “reasonable basis” for war crimes—including willful killing, torture, and rape—but closed the probe, citing insufficient evidence of UK “shielding” by authorities.

“The UK investigative and prosecutorial bodies had not engaged in shielding,” her office concluded in a 184-page analysis.

Rights advocates decried it as a whitewash. “The UK government has repeatedly shown precious little interest in investigating… atrocities,” said Clive Baldwin of Human Rights Watch, warning of a “double standard” favoring powerful nations.

Evidence of abuses is irrefutable. In 2005, three soldiers were court-martialed in Germany, convicted on photographic proof, and discharged.

Corporal Donald Payne, in 2007, drew a year in prison for his role in Mousa’s death—the first British conviction for Iraq-related mistreatment.

ECCHR’s 2020 dossier detailed a “pattern” of violence, corroborated by Iraqi testimonies.

Featherstone attributes Blair’s ICC optimism to pre-war negotiations ensuring the court deferred to national systems.

Yet, he notes biases: the ICC’s resource constraints and focus on weaker states. “It’s certainly true that the ICC has historically been accused of being biased,” he said.

Blair’s interventions, per the files, extended to broader war optics. Frustrated by legal qualms from officials, he prioritized alliance with the US in the “war on terror.”

The UK deployed 46,000 troops alongside 100,000 Americans, dwarfing contributions from allies like Australia (2,000) and Poland (194).

Today, as the war’s 23rd anniversary nears, these revelations fuel calls for accountability. Anti-war protesters, who massed outside Parliament in 2003, see vindication.

“Blair’s legacy is one of deception and deflection,” said one veteran demonstrator. With Trump eyeing a 2025 return and Middle East tensions simmering—from Gaza to Yemen—the Iraq file warns of enduring costs of unchecked power.

Blair, now 72 and a global consultant, has not commented on the release. His office declined requests, citing privacy. But in UK politics, where Iraq symbolizes hubris, the archives ensure his shadow lingers.

Discover more from AMERICA NEWS WORLD

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a Reply