By_shalini oraon

_the slight ‘dip’ in early-November pollution in Delhi, exploring the data, the causes, and the critical context behind the numbers.

—

A Fleeting Respite: Decoding the Significance of Delhi’s Early-November Pollution Dip

Each year, the calendar’s turn to October sends a wave of apprehension through India’s capital. The air grows heavy, the horizon blurs, and the familiar, acrid taste of smoke returns—the annual pollution season in Delhi is as predictable as it is devastating. Yet, in early November of this year, a curious headline emerged from the usual grim narrative: data indicated a slight ‘dip’ in pollution levels. This statistical glimmer, however minor, demands a closer look. Was this a sign of successful policy, a meteorological fluke, or merely a pause in the city’s relentless descent into toxic air? The answer is a complex cocktail of all three, revealing both the potential for change and the immense challenge that remains.

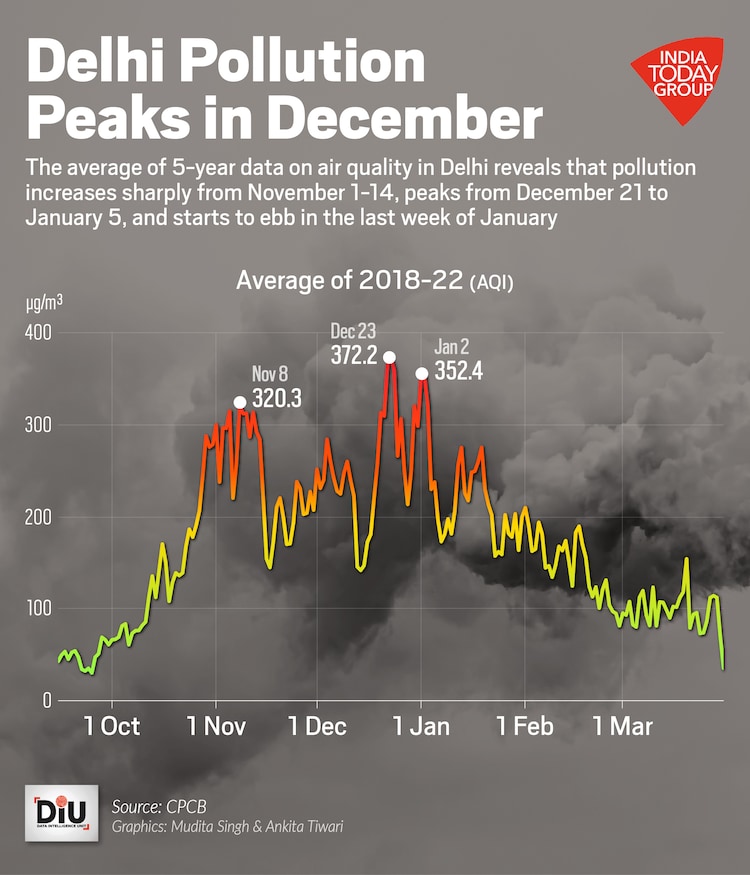

The data, compiled from the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) and independent monitors like the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), told a clear, if modest, story. Compared to the same period in previous years—particularly the catastrophic post-Diwali spikes that have become commonplace—the first week of November showed a 10-15% reduction in the concentration of PM2.5, the most dangerous microscopic particulate matter. The Air Quality Index (AQI), while still largely in the ‘Poor’ to ‘Very Poor’ category, had fewer excursions into the ‘Severe’ zone. This deviation from the worst-case scenario was not a move toward clean air, but rather a avoidance of the absolute peak of pollution. To understand why, one must examine the confluence of factors that briefly held the smog at bay.

The Meteorological Reprieve: Nature’s Intervention

First and foremost, the dip was a gift from the weather. Delhi’s pollution crisis is a tale of two parts: emissions and meteorology. The city generates a massive baseline of pollution year-round from its vehicles, industries, and power plants. But it is the autumn and winter weather that acts as a lid, trapping these pollutants and allowing them to accumulate to lethal concentrations.

This early November, that lid was slightly ajar. The wind speed, a critical dispersing agent, was marginally higher than in previous years. While not strong enough to scour the air clean, these breezes were sufficient to prevent the stagnant conditions that lead to rapid pollutant build-up. Furthermore, the mixing layer height—the altitude at which pollutants can disperse vertically—was slightly more generous. A low mixing layer height acts like a low ceiling in a room filling with smoke, concentrating the toxins near the ground. A slightly higher one provides a larger “room” for dilution. These minor meteorological advantages were crucial. They underscore a sobering reality: even a small favorable shift in weather can have a measurable impact, highlighting how precariously balanced Delhi’s air quality is.

The Policy and Action Factor: A Deliberate, if Partial, Effort

To attribute the dip solely to the weather would be to ignore the deliberate, if often criticized, efforts of policymakers. In the weeks leading up to the predicted pollution peak, a series of measures were implemented under the central government’s Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP).

The most significant of these was a concerted, if uneven, crackdown on stubble burning in the neighbouring states of Punjab and Haryana. Satellite data from the NASA-based Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) showed a noticeable, though not drastic, reduction in farm fire counts during this period. This can be attributed to a combination of factors: increased machinery availability for in-situ management of paddy straw, some financial incentives for farmers, and heightened political pressure. While the problem is far from solved, a marginal reduction in this major external source of pollution during the peak burning period had a tangible effect on Delhi’s air.

Within the city, efforts to enforce dust control norms at construction sites and to regulate traffic flow were more visible than in previous years. The “Red Light On, Gaadi Off” campaign and the ongoing push for public transport, while facing compliance issues, contributed to a marginal reduction in the vehicular load. These actions did not eliminate emissions, but they may have shaved off the worst of the peak, working in tandem with the helpful weather to create the observed dip.

The Crucial Context: A Dip, Not a Solution

This is where the narrative must be tempered with stark reality. Celebrating this dip as a victory would be a profound mistake. The “improvement” was relative only to the catastrophic baseline of previous years. An AQI of 280 (‘Poor’) is still dangerously unhealthy, posing risks to the young, the elderly, and those with respiratory conditions. The dip was a movement from “severe crisis” to “severe problem.”

Furthermore, the transient nature of the improvement reveals its fragility. The systems that created this minor success are not yet robust enough to withstand less favorable conditions. A subsequent period of calmer winds and lower temperatures could—and likely will—quickly erase these gains, pushing the city back into the ‘Severe’ category. The fundamental problem remains unaddressed: Delhi’s economy and infrastructure are fundamentally polluting. The number of vehicles continues to grow, the reliance on fossil fuels for energy and industry persists, and the complete solution to the agricultural waste issue remains elusive.

Conclusion: A Blueprint in a Glimmer

The early-November dip in Delhi’s pollution is therefore a story with a dual moral. It is, on one hand, a demonstration that coordinated action can yield results. It proves that reducing stubble burning, controlling dust, and managing traffic can, when aided by nature, prevent the very worst air quality events. This provides a valuable, data-driven argument for environmental groups and progressive policymakers to demand the scaling up of these efforts.

On the other hand, it is a stark warning against complacency. The battle for breathable air in Delhi is not going to be won by achieving slightly less terrible outcomes. It requires a fundamental restructuring of urban mobility, energy generation, and regional agriculture. The dip was a fleeting respite, a momentary clearing of the smoke that allowed a glimpse of the monumental task ahead. The data shows that progress is possible, but it also screams that the current pace and scale of action are woefully inadequate. The true significance of the early-November dip is not that the air was better, but that it revealed, with painful clarity, just how far there is left to go.

Discover more from AMERICA NEWS WORLD

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

![Smoke rises after Israeli strikes in Beirut's southern suburbs, on March 2 [Mohamad Azakir/Reuters]](https://america112.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/03/hgh.webp)