By Manisha Sahu | America News World | October 30, 2025

Herat, Afghanistan — On a rooftop in Herat city, a blue tarpaulin tied to four bamboo poles flaps under the wind. Beneath it, Soheila*, her husband, and their two small children huddle together, trying to shield themselves from the cold Afghan nights. The makeshift tent is their only shelter — a temporary refuge after being forced to return from Iran, where they had lived for five years.

Soheila’s husband once worked as a construction labourer in Esfahan, Iran, while she stitched clothes at home to make ends meet. But when the Iranian authorities intensified deportations earlier this year, the family had no choice but to return to Afghanistan — a homeland they no longer recognize.

“We looked everywhere for a house,” Soheila says softly. “But with what little money we had and my husband out of work, it was impossible. Even on the outskirts of Herat, rents are between 5,000 and 7,000 afghanis a month. When a man earns 10,000 at most, how can a family survive?”

Her sister’s small home, already crowded with eight people in two rooms, is their only sanctuary. Yet even that space feels temporary. “We can’t stay here forever,” she says, glancing at the plastic sheets overhead. “But where else can we go?”

A Wave of Returnees

Soheila’s story is just one among millions. Since April 2025, more than 1.4 million Afghans have returned from Iran, according to data from the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR). Combined with deportations and forced returns from Pakistan, the total number of Afghan returnees this year has crossed 2.2 million — marking the largest wave since the Taliban takeover in 2021.

For many, the return is not voluntary. Iranian authorities have tightened their policies, citing national security and economic strain. Across border crossings like Dogharoun, Milak, and Islam Qala, hundreds of buses packed with weary families arrive daily. They carry only what they can fit into a few bags — blankets, cooking pots, and memories of the lives they left behind.

“Most of these families are coming back under distress,” says a UNHCR field officer in Herat. “They are being expelled or pushed to leave due to increasing restrictions. The challenge now is not just their arrival — it’s what happens afterward.”

A Second Displacement

The mass influx of returnees has overwhelmed Afghan cities already struggling with economic collapse, rising inflation, and an acute housing shortage. With limited jobs and soaring rent prices, thousands of families find themselves without a roof over their heads.

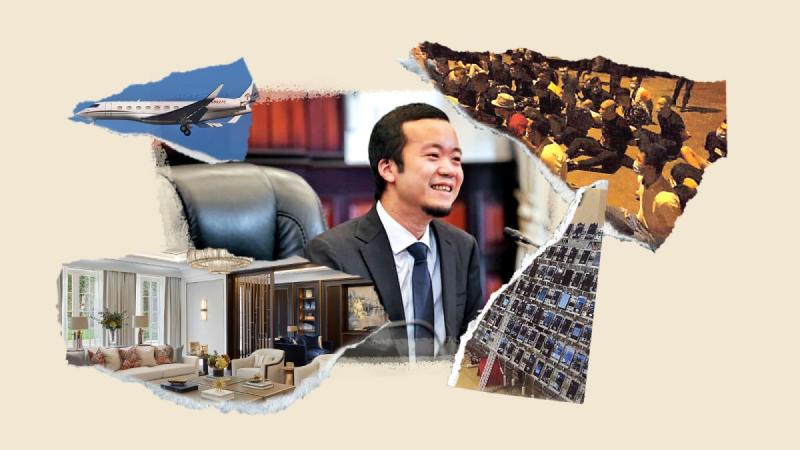

Public parks in Kabul and Herat have turned into makeshift camps, with rows of plastic tents and shanties. In some areas, abandoned buildings have been converted into temporary shelters. Local aid workers estimate that nearly 60% of returnee families are either homeless or living in informal settlements.

“Afghanistan is facing a double crisis,” explains Dr. Rahimullah Niazi, an urban development researcher in Kabul. “The country lacks affordable housing, and now hundreds of thousands of people are returning every month. It’s a humanitarian emergency that’s being overlooked.”

In Herat, landlords have taken advantage of the growing demand. Rents that once stood at 3,000 afghanis have now doubled or even tripled. For daily wage earners who make less than 400 afghanis ($5) a day, a permanent home is simply out of reach.

Aid Under Pressure

At the Islam Qala border, where thousands cross daily, humanitarian agencies are stretched thin. UNHCR and its local partners provide returning families with basic items — blankets, gas cylinders, water jerry cans, and food supplies — but the resources are running low.

“Our funding is shrinking, but the number of people in need keeps rising,” says a representative from the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), which works alongside UNHCR in western Afghanistan. “We can offer immediate relief, but long-term housing solutions are beyond our capacity.”

International aid to Afghanistan has declined sharply since the Taliban’s return to power. Many donors suspended or reduced funding amid concerns over human rights and restrictions on women’s work and education. As a result, vital shelter and livelihood programs have been scaled back.

Meanwhile, the Afghan government’s capacity to address the crisis remains limited. With frozen foreign reserves, an economy in freefall, and unemployment above 30%, even basic public services are faltering.

From Hope to Hardship

For returnees like Soheila, the emotional toll is as heavy as the financial one. “In Iran, life was hard, but at least we had a roof and food,” she says. “Here, we have nothing. We thought we were coming home — but it feels like another exile.”

Her story is echoed by hundreds of others in Herat’s crowded neighborhoods. Some families have sold their few remaining possessions to pay rent; others have moved in with relatives, deepening the strain on already poor households. Women who once worked in Iran are now confined to homes due to restrictions under Taliban rule, losing a vital source of income.

Children, too, face uncertainty. Many returnee families struggle to enroll them in schools because of documentation issues or lack of capacity. “It’s not just a housing problem,” says aid worker Fatima Ahmadi. “It’s a crisis that touches every part of life — education, health, and dignity.”

A Looming Winter Threat

As winter approaches, the situation could worsen dramatically. Western Afghanistan experiences harsh cold from November onward, and aid groups warn of rising deaths due to exposure and malnutrition.

UNHCR and UNICEF have appealed for emergency funding to supply winterization kits — including warm clothing, stoves, and tents — to vulnerable families. But without significant international support, millions remain at risk.

“Winter is our biggest fear,” says Soheila. “The tarpaulin won’t protect us from the snow. I pray my children don’t fall sick.”

A Humanitarian Crossroads

The return of Afghan refugees from Iran and Pakistan underscores a deeper global dilemma: what happens when displaced people have nowhere safe to go. For decades, Afghans have been among the world’s largest refugee populations, with millions seeking safety abroad. Now, as neighboring countries push them back, Afghanistan itself offers little refuge.

Experts warn that without coordinated international action, the crisis could spiral into a long-term catastrophe. “If we don’t address housing and livelihoods for returnees, we’ll see mass urban poverty, rising homelessness, and further instability,” says Dr. Niazi. “It’s not just Afghanistan’s problem — it’s a regional and global one.”

For Soheila and countless others, the future remains uncertain. Her family still sleeps under the tarpaulin each night, listening to the city’s quiet hum. “We came back because we thought we belonged here,” she says. “But now, we ask ourselves — where else can we go?”

* Name changed for privacy.

Discover more from AMERICA NEWS WORLD

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a Reply