By Alex Rivera

America News World

October 13, 2025

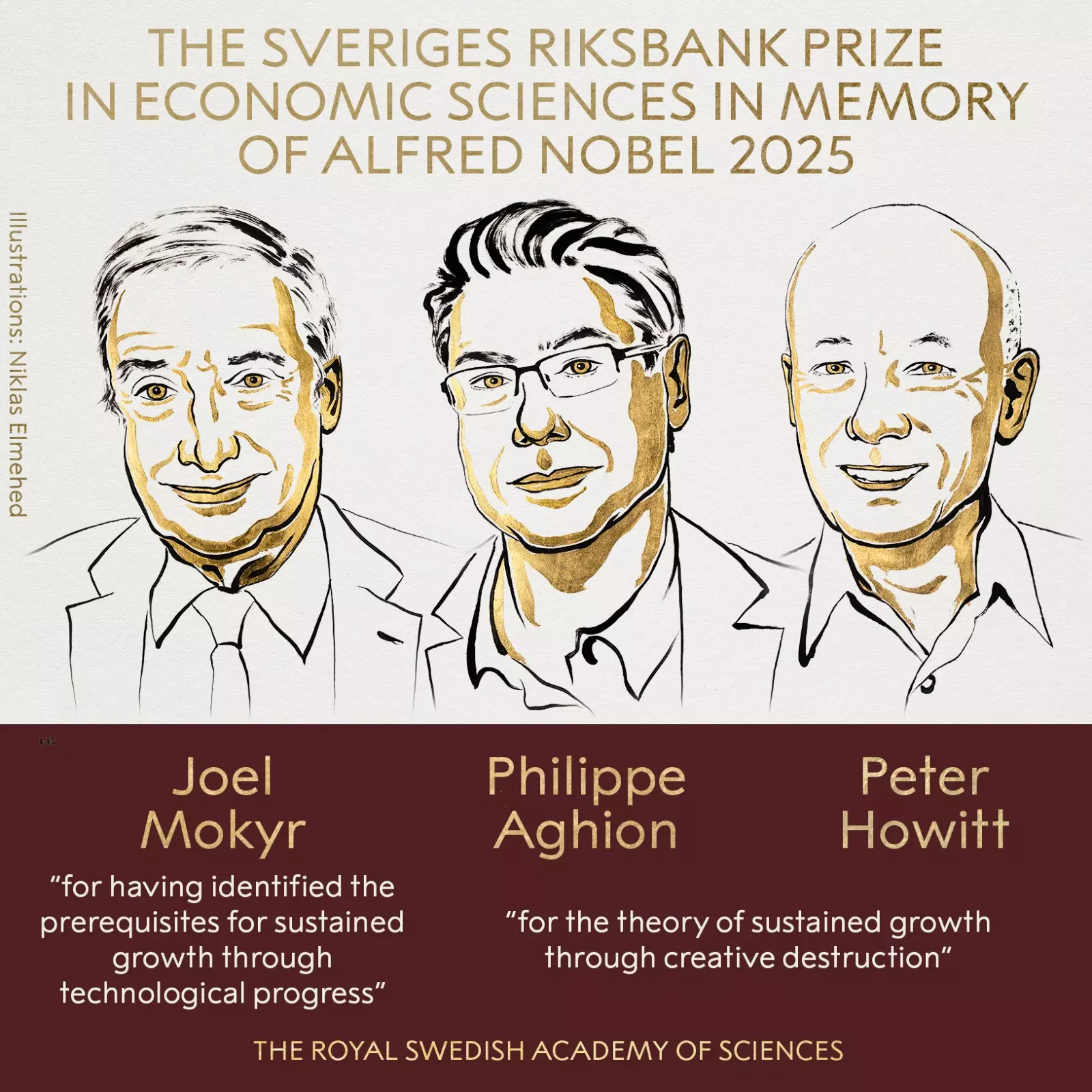

In a world full of fast changes like AI and green energy, three smart economists just won the biggest prize in their field. On October 13, 2025, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences gave the Nobel Prize in Economics to Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt. They got it for showing how new ideas and inventions make economies grow strong and help people live better lives.

This prize, called the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel, is worth 11 million Swedish kronor, or about $1.2 million. Half goes to Mokyr, and the other half is shared by Aghion and Howitt. It’s the last Nobel of the year, after prizes for medicine, physics, chemistry, peace, and literature.

The winners come from top schools in the U.S., France, and the UK. Joel Mokyr teaches at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. Philippe Aghion works at College de France and INSEAD in Paris, plus the London School of Economics. Peter Howitt is at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island.

Their big idea? Innovation – that’s creating new stuff like better phones or machines – is the key to why countries get richer. But it’s not always easy. New things often “destroy” old ways, like how smartphones killed old landline phones. This mix of creating and breaking is called “creative destruction.” The Nobel group said the winners explained how this process started big growth in the last 200 years, pulling billions out of poverty.

For most of history, people lived the same way. Farms stayed small, tools didn’t change much, and life was hard. Growth happened now and then, like with the wheel or printing press, but it stopped fast. No one knew why new things worked, so they couldn’t build on them. Economies stayed flat, and most folks were poor.

Then came the Industrial Revolution around 1750 in Europe. Machines for spinning cotton, steam engines, and factories changed everything. Why? Joel Mokyr’s books, like A Culture of Growth from 2016, say it was because people started asking “why” and sharing knowledge. Science grew, and societies let new ideas in. No more kings or churches blocking change. Europe had many small countries, so thinkers could move if one place said no.

Mokyr, born in 1946 in the Netherlands, moved to Israel as a kid and got his PhD from Yale in 1974. He’s written over 20 books on Europe’s economic history from 1750 to 1914. He says open minds and free talk are musts for progress. Without them, we go back to old, slow days.

Data backs this up. Before 1800, world GDP per person grew less than 0.1% a year. After the Industrial Revolution, it jumped to 1-2% in rich countries, and now global average is about 2.5%. That’s why today’s average person has 10 times more stuff than in 1820. The World Bank says extreme poverty fell from 90% of people in 1820 to under 10% now, thanks to this growth.

Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt took it further with math. In 1992, they wrote a famous paper, “A Model of Growth Through Creative Destruction.” It uses equations to show how new products beat old ones in the market. Think of Kodak losing to digital cameras from startups. The winners get rich, but old companies shrink or die. This “destruction” hurts at first – jobs lost, towns empty – but it pushes everyone to try harder.

Aghion, born in 1956 in Paris, got his PhD from Harvard in 1987. Howitt, born in 1946 in Canada, studied at Northwestern and got his PhD there in 1973. Their model says growth speed depends on how easy it is to invent and how much power winners get from patents. More competition means faster change, but too much blocks big risks.

They built on Joseph Schumpeter, an Austrian thinker from the 1940s. He called creative destruction “the essential fact of capitalism.” It’s like a storm that clears old trees for new ones to grow tall.

Numbers show the power. A study by economists like Leonid Kogan found that big jumps in inventions add 0.6% to 6.5% to yearly GDP growth. In the U.S., creative destruction explains about 25% of job changes, per NBER data from 2017. Young firms create 3 million jobs a year, while old ones lose 3 million – but net, jobs grow 2%. In manufacturing, new tech reallocation boosts productivity by 2-3% yearly, says a 2004 study across 24 countries.

This matters today. AI could spark huge growth, like the internet did in the 1990s, adding trillions to the world economy. But winners worry about roadblocks. Aghion said at the press event: “De-globalization and tariffs are obstacles to growth. Bigger markets mean more idea-sharing and competition.” He wants Europe to copy the U.S. and China, mixing rules with help for key areas like defense, climate, and biotech. Europe got too strict on “industrial policy,” he says, and now lags in AI.

Howitt slammed U.S. President Donald Trump’s trade plans. “Tariffs shrink markets and slow innovation,” he told reporters. “Bringing back factory jobs sounds good politically, but it’s bad economics. We’re great at design, let others make the shoes.” Trump’s tariffs, started in 2018 and maybe more now, could cut U.S. growth by 0.5%, per some models.

Mokyr agrees: Societies must stay open. He lists three blocks to new tech – powerful old bosses, fear of big changes, and worry about unknowns. Politics often sides with the past, like blocking self-driving cars over safety fears.

The downsides are real. Creative destruction kills jobs fast. In the U.S., 5-10% of workers switch jobs yearly from this, per Federal Reserve data. Coal towns in America or steel mills in the UK suffered when imports or machines took over. Inequality rises if winners grab too much, as 2024 Nobel winner Simon Johnson noted.

But overall, it’s a win. Long-term, it lifts boats. Health improved – life expectancy doubled since 1800. Travel, food, fun – all better. Climate change is the big test now. Can we destroy dirty coal for clean solar without chaos? The winners say yes, if we plan smart.

This prize reminds us: Growth isn’t magic. It needs schools, free trade, and guts to let old ways go. As John Hassler, the prize chair, said: “We must protect creative destruction, or risk stagnation.”

The Nobel started in 1901 from Alfred Nobel’s will, the dynamite guy. Economics joined in 1969. Past winners include Paul Krugman on trade and Ben Bernanke on crises. Only three women so far, a sad stat.

For America, it’s a call to action. We’re innovation kings – Silicon Valley, SpaceX – but tariffs and fights could slow us. Europe eyes our lead, China pushes hard. To keep growing, stay open, fund science, and embrace the destroy part.

This news from Stockholm hits home in a shaky world. With wars, climate woes, and AI unknowns, these economists say: Innovate or fade. Their work isn’t just books – it’s a map for tomorrow

Suggested Reading:

- Nobel Press Release: nobelprize.org

- World Bank Data on Poverty: worldbank.org

- NBER on Jobs: nber.org

Alex Rivera covers global economics for America News World. Reach him at alex@anwnews.com.

Discover more from AMERICA NEWS WORLD

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a Reply