By_shalini oraon

—

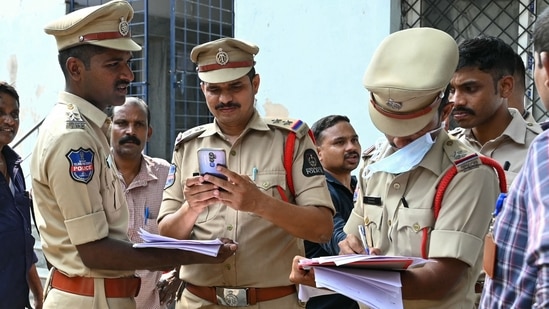

‘No Time to Rest’: The Overworked Guardian of Democracy in Rural Bengal

The humid Bengal air hangs heavy, not just with the promise of the monsoon, but with the immense weight of democratic duty. In a small, spartan room of a school-cum-polling-station in a village in Cooch Behar, the clock ticks with a metronomic urgency that mirrors the rhythm of Animesh Roy’s heart. A slip of paper, a “SIR” (Subject Information Report), has just been handed to him, and for a moment, the already Herculean task of managing the upcoming election collides with the unyielding demands of his own life. Animesh, a 45-year-old government clerk, is one of the thousands of unsung foot soldiers of Indian democracy—a village polling staffer for whom the election is not a single day of voting, but a gruelling marathon of logistics, pressure, and personal sacrifice.

The phrase “No time to rest” is not a complaint from Animesh’s lips; it is a simple, stark statement of fact. His journey as a Presiding Officer for this election began weeks ago, with a formal letter that felt more like a summons. Since then, his life has been bifurcated. By day, he juggles his regular clerical job, a role with its own set of targets and bureaucratic deadlines. By night, and in every stolen moment in between, he becomes an election administrator. His small government quarter has been transformed into a war room. The dining table is buried under training manuals, indelible ink vials, and the sacred, multi-layered forms—Form 17A, 17C, 17D—that are the scripture of the electoral process.

“The training sessions are exhaustive,” Animesh explains, his voice a low, steady hum. “We are taught everything: how to handle the EVM, how to deal with aggressive voters, how to identify proxy voting, how to fill the forms without a single error. A single mistake, and the entire polling booth’s result could be questioned. The responsibility is terrifying.” This weight is compounded by the political atmosphere. In the villages of Bengal, elections are not polite disagreements; they are deeply personal, often visceral contests of identity and allegiance. As a neutral government servant, Animesh must navigate this charged environment, a task requiring the patience of a saint and the tactical acumen of a field general.

Just as he was finalizing the logistics for the dispatch of polling materials, the SIR arrived. It was a routine administrative notice concerning a property dispute his family was involved in, requiring his presence and documentation. For most, this would be a significant life stressor. For Animesh, it felt like a cosmic test. “There is no space for this right now,” he says, a flicker of exhaustion crossing his face. “My mind is consumed with ensuring the polling party reaches on time, that the EVMs are sealed correctly, that the mock poll is conducted flawlessly. Now I have to find time, a time that does not exist, to deal with this SIR. It feels like juggling knives while walking a tightrope.”

This collision of the personal and the professional is the untold story of Indian elections. The electoral machinery, a behemoth that successfully orchestrates the world’s largest democratic exercise, is powered by individuals like Animesh, whose own lives are put on hold. His wife handles the children’s school routines and the mounting domestic worries, his own small agricultural plot lies unattended, and the SIR sits on his desk, a silent, ticking reminder of a life waiting to be lived.

The day before the poll is a controlled frenzy. Animesh and his three polling officers gather at the distribution centre. The air is thick with anxiety and purpose. EVMs are allocated and checked with ritualistic solemnity. The seals are affixed, the paperwork is cross-checked. Animesh moves with a calm authority, a mask he wears to instill confidence in his team. But internally, he is running through a mental checklist, the SIR a nagging background hum. “Did I remember to tell my wife where the documents for the SIR are? Will I be able to get a day’s leave after the poll to address it?”

Polling day itself is a 24-hour blur that begins long before sunrise. By 4 a.m., Animesh and his team are at the booth, arranging furniture, setting up the voting compartments, and preparing for the 7 a.m. opening. As the sun rises, so does the din of democracy. Voters stream in—the elderly supported by relatives, first-time voters with a mix of nervousness and pride, party agents with hawk-like eyes watching every move. Animesh is the conductor of this chaotic orchestra. He verifies identities, resolves disputes over spelling errors on voter rolls, ensures the indelible ink is applied correctly, and maintains order. A scuffle breaks out between two rival party workers; he intervenes with a firm, neutral tone, de-escalating the situation before it spirals.

The physical toll is immense. There is no comfortable chair, no proper meal break. He eats a hurried lunch of rice and lentils out of a tiffin box, one eye always on the polling process. The mental toll is greater. Every decision is scrutinized, every action potentially contentious. He thinks of the SIR, of the unresolved issue at home, and pushes the thought away. There is no room for it here, in the sanctum of the polling station.

Finally, at 5 p.m., the voting ends. But Animesh’s duty does not. The most critical phase begins—the sealing of the EVMs and the accounting of every single vote and form. Under the watchful eyes of the candidates’ agents, he supervises the process, reading out each step aloud. A single misstep here could invalidate the day’s labour. It is past midnight by the time the EVMs are securely stored in the strongroom and the final report is submitted to the returning officer. The physical exhaustion is total, but a profound, quiet satisfaction begins to seep in.

He returns home as the next day is dawning. He collapses onto his bed, his body aching, his mind still racing with images of forms and queues. The SIR is still on his desk. The property dispute still needs resolving. His regular job awaits him after a single day’s reprieve. There is, truly, no time to rest.

Animesh Roy’s story is a microcosm of the Indian election. The sleek EVMs, the voter turnout percentages, the political victories and defeats, all rest on the weary shoulders of countless anonymous civil servants. They are the guardians of the process, the human infrastructure that ensures the will of the people is recorded, one vote at a time. They juggle life, duty, and personal crises as the clock ticks, asking for nothing in return but the successful, peaceful completion of a task they see as a sacred covenant with their nation. In their tireless dedication, even amidst their own struggles, lies the enduring resilience of the Indian democratic ideal.

Discover more from AMERICA NEWS WORLD

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a Reply