By Suraj Karowa and Thomas Page/ ANW

Tokyo, December 8, 2025

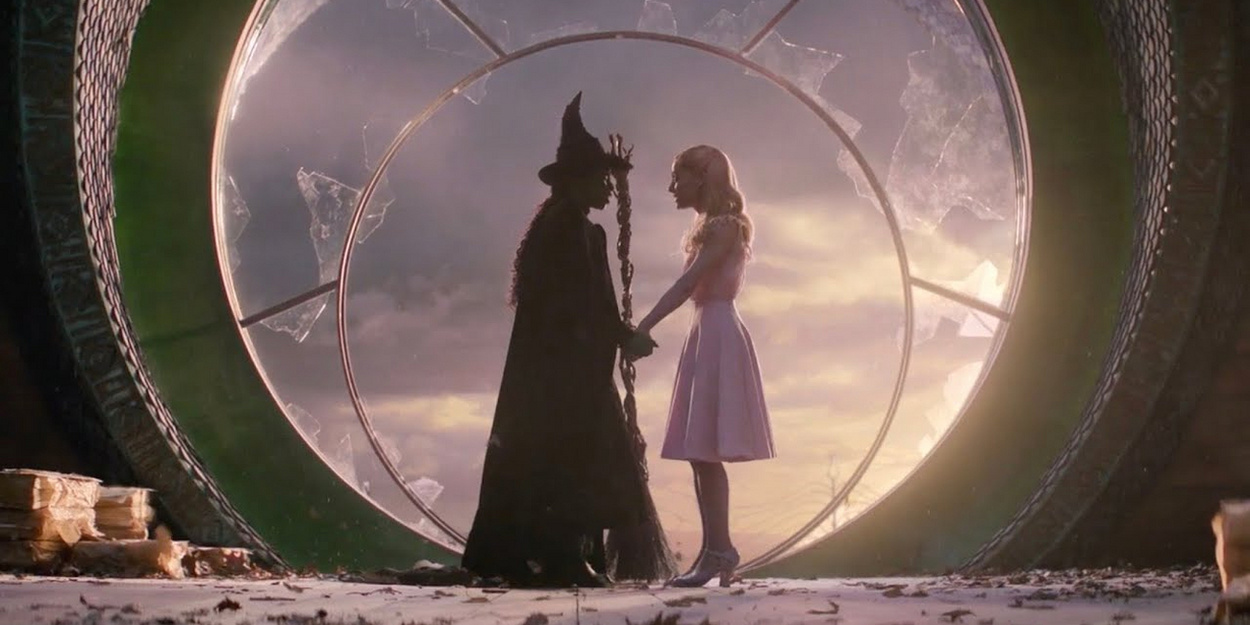

Ryo Yoshizawa and Ryusei Yokohama as Kikuo and Shunsuke, rival kabuki actors in Japanese Oscar submission “Kokuho.”

In the opulent glow of Tokyo’s Kabuki-za Theatre, where painted faces and silk robes have mesmerized audiences for centuries, a quiet crisis unfolds.

The 400-year-old art form—once Japan’s beating heart of drama, dance, and spectacle—fades into obscurity.

Attendance at national venues lingers below pre-pandemic highs, apprentices dwindle, and the thunderous applause of yesteryear echoes faintly. Yet, a cinematic phenomenon may just rewrite this elegy.

Enter Kokuho, a sweeping three-hour saga that traces half a century in the life of a fictional kabuki maestro.

A pedestrian walks past a poster of a kabuki actor in Tokyo on March 6, 2022. Attendance at kabuki performances at National Theatres in Japan have not bounced back to pre-pandemic levels.

Directed by Lee Sang-il (Pachinko) and adapted from Shuichi Yoshida’s acclaimed novel, the film has shattered box office records, grossing $111 million in Japan alone—crowning it the highest-earning live-action Japanese film ever.

Debuting at Cannes in May, it’s now Japan’s official entry for the 2026 Academy Awards’ Best International Feature, riding the wave of distributor GKIDS’ recent triumph with Studio Ghibli’s The Boy and the Heron.

More than a blockbuster, Kokuho—translating to “national treasure”—mirrors the real-world plight of kabuki, a UNESCO intangible cultural heritage.

Data from the Japan Arts Council reveals stark declines: theater footfall at flagship venues like the National Theatre hasn’t rebounded from COVID-19 lows, hovering at 60% of 2019 levels.

The apprentice pipeline, once sustained by familial dynasties, runs dry; the National Theatre Training School, which has schooled a third of today’s performers, drew only two applicants for its latest two-year program.

Yoshizawa’s character performs as an “onnagata” – a male actor playing female roles, a tradition of kabuki stretching back hundreds of years.

“Kabuki isn’t dying,” insists a council spokesperson, speaking on condition of anonymity amid internal deliberations. “But it’s evolving—or it must. Kokuho feels like a catalyst.”

The film’s protagonist, Kikuo (Ryo Yoshizawa), embodies this tension. Orphaned son of a yakuza enforcer, the 15-year-old outsider—already “old” by kabuki’s rigorous standards—enters the fray under the wing of veteran Hanjiro (Ken Watanabe).

Rivalries ignite with Hanjiro’s son Shunsuke (Ryusei Yokohama), as Kikuo masters the “onnagata” role: male actors channeling ethereal femininity, a 17th-century convention demanding precise glides, gestures, and grace.

Yokohama and Yoshizawa in “Kokuho.” The film is a box office hit in Japan, where it is the highest grossing Japanese live action film of all time.

Yoshizawa, 31, immersed himself for 18 months. “Three months on suriashi alone—the sliding walk that whispers across stages,” he recounts in a Tokyo cafe, mimicking the subtle shift of weight.

“Then dance: hips swaying like willow branches, fans flicking secrets. Real kabuki artists train lifetimes; I chased shadows.”

On screen, Kikuo’s ascent dazzles: from smoky backroom brawls to spotlighted soliloquies of love, betrayal, and transfiguration.

The script weaves kabuki classics—tales of star-crossed lovers and ritual suicides—into Kikuo’s psyche, offering subtitles for novices. “Even Japanese audiences rarely know the repertoire cold,” Lee notes via translator.

“We demystify without dumbing down.”

Cinematographer Sofian El Fani (Blue Is the Warmest Color) bridges stage and screen, zooming into quivering fingers that betray inner turmoil.

The film follows Kikuo for around 50 years through the highs on lows of his journey toward the title of “living national treasure.”

“It’s opera meets Shakespeare,” Lee says. Off-stage, yakuza clashes adopt theatrical blocking—exaggerated poses, rhythmic clashes—blurring life’s grit with art’s grandeur.

By 2014, Kikuo—aged via prosthetics and posture—gazes at a fractured legacy: jealous foes, forsaken loves, a title of “living national treasure” that feels hollow.

Yoshizawa nails the nuance: onnagata elders defy time, their spines unbowed, faces powdered eternal youth. “It’s not just aging,” he says. “It’s aging as art—poised, unbroken.”

Kokuho’s triumph has electrified kabuki circles. Local buzz swirls: performers whisper of packed post-screening discussions.

In September, when Nakamura Ganjiro IV—a film cameo and coach—joined Lee at the National Theatre, 2,200 vied for 100 seats.

“Interest surges, especially youth,” the Arts Council reports. No hard metrics yet, but anecdotal sparks abound: social media hashtags like #KokuhoKabuki trend, blending fan edits with historical clips.

Seizing momentum, the council rolls out flyers at cinemas, a January 2026 tie-in festival with discounted “newcomer” seats, and beginner workshops.

“Flyers say: ‘See the film, live the stage,'” the spokesperson adds. The training school, flooded with Kokuho-inspired queries, ponders outreach tweaks—perhaps virtual previews or age-flexible trials.

Lee marvels at the ripple. “I expected acclaim, not revolution. Audiences crave beauty amid chaos—effort, transcendence. Yoshizawa’s grit mirrors kabuki’s soul: pushing limits for fleeting glory.”

Yoshizawa echoes: “Persevering through inadequacy? That’s Kikuo. That’s kabuki.”

Revival isn’t assured. Kabuki’s barriers—stiff etiquette, archaic language, ticket prices rivaling symphonies—deter casuals.

Yet initiatives proliferate: family classes, under-30 discounts, English audio guides for tourists. Dynasties endure; this year, Onoe Kikugoro VII’s name-taking rite anointed his lineage anew.

As Kokuho eyes Oscars—potentially the first kabuki-centric nod—its legacy may transcend reels. In a Japan grappling globalization’s pull, it spotlights heritage’s pullback.

Will screens summon crowds to cedar stages? Early signs whisper yes: a theater once niche, now knocking on youth’s door.

For now, in Tokyo’s neon haze, a poster of Kikuo’s painted gaze beckons. Walk inside, and perhaps kabuki slides forward—one suriashi at a time.

Discover more from AMERICA NEWS WORLD

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a Reply