By Scarlett Harris , Suraj Karowa/ANW

Culture | November 28, 2025

In The Ingoldsby Legends (1907) Arthur Rackham’s illustrations portray the sorceress in black cloak and tall black hat.

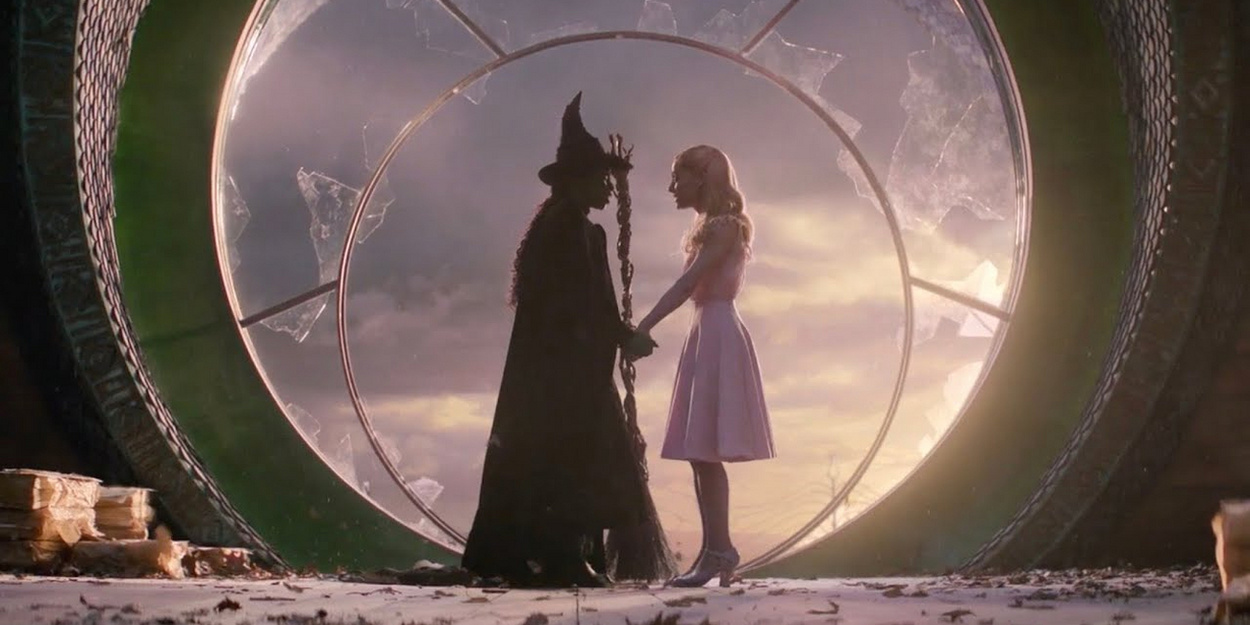

As the curtain rises on Wicked: For Good, the electrifying sequel to the blockbuster musical adaptation, Cynthia Erivo’s Elphaba once again soars into theaters, her signature black conical hat defying gravity alongside her emerald-skinned defiance.

But this towering headpiece—equal parts menace and majesty—is no modern invention.

Its roots stretch back millennia, evolving from symbols of divine power to tools of persecution, and finally to emblems of feminist rebellion.

With the film’s release hot on the heels of Halloween’s witch-craze, it’s a timely moment to trace how the “hideodeous” hat, as Glinda sneers in the story, became the ultimate witch archetype.

Tall pointy hats – otherwise known as capirotes or corozas – were used in history as a tool of persecution.

Picture the first flickers of this motif: not in foggy European forests, but in the sun-baked Bronze Age, around 2000 BCE.

Archaeologists unearthed golden, tapered crowns adorned with celestial motifs in ancient tombs from the Eurasian steppes.

These weren’t mere accessories; they crowned priests believed to channel cosmic wisdom.

Fast-forward to China’s Tarim Basin, where mummies from the 4th to 2nd centuries BCE—dubbed the “Witches of Subeshi” after their 1978 discovery—wore similar pointed hats.

Witches’ Flight by Francisco Goya (1798) portrays three floating figures in tall, conical hats carrying a man aloft.

Their felted, feather-trimmed cones suggested shamanic roles, blending reverence with the arcane.

Witches’ brew

In these early iterations, the hat signified enlightenment, not evil—a far cry from today’s Halloween staple.

Centuries later, the shape took a darker turn, weaponized by religious orthodoxy. In 13th-century Europe, the Roman Catholic Church mandated the Judenhut for Jewish men: a yellow, horned cone meant to mark and marginalize.

It was a badge of “otherness,” echoing broader edicts against non-conformists. The Spanish Inquisition, launched in 1478, amplified this cruelty.

The earliest known depiction of a witch in a black pointed hat is from 1693.

Accused of heresy, blasphemy, or witchcraft, prisoners donned capirotas or corozas—tall, tapered hoods of infamy.

These weren’t just hats; they were public spectacles of shame, paraded through streets to deter dissent.

The invisible world

Though the capirote endures today in Spain’s Holy Week processions as a penitential symbol, its inquisitorial shadow lingers.

Could this legacy have seeded the witch-hat trope? Historians debate it, but the visual parallel is striking.

In the 17th Century, tall black pointy hats were everywhere – shown here, Portrait of Mrs Salesbury with her Grandchildren.

Art captured the shift. Francisco Goya’s 1798 Witches’ Flight—a satirical jab at Enlightenment-era superstitions—depicts airborne crones in lofty cones hauling a hapless man skyward.

Their hats evoke both ecclesiastical mitres and inquisitorial corozas, while a donkey below nods to folly.

Goya’s grotesque figures, with their wild features and ignorant onlookers, mock the hysteria that once fueled witch hunts. Yet, the motif’s ties to actual sorcery are murkier.

Enter the Middle Ages’ unsung heroines: alewives. These women brewed ale in conical hats to advertise their wares at markets—their tall brims kept steam from singeing brows and signaled their stalls from afar.

Portrait of Esther Inglis (1571-1624) by an unknown artist depicts the fashionable headwear of the time.

With cauldrons bubbling herbs for both beer and remedies, they embodied “wise women” versed in folk medicine.

Superstition branded them suspect; as beer historian Jane Peyton notes in A Woman’s Place Is in the Brewhouse, brewsters joined herbalists in the “othered” ranks eyed warily by the uneducated.

Reclaiming the witch

But Dr. Laura Kounine, early modern history expert at the University of Sussex, calls this link “a bit of a myth.”

Cauldrons were kitchen staples, brooms household tools, and hats? Ubiquitous, if not always pointy.

What truly set witches apart in 16th-century art, she argues, was unveiled hair—loose locks screaming moral chaos in an era when covered tresses denoted propriety.

Costume designer Paul Tazewell has reinterpreted the “hideodeous” hat for the new film Wicked: For Good.

Albrecht Dürer’s Witch Riding Backwards on a Goat (1501–02) and Hans Baldung Grien’s The Witches’ Sabbath (1510) show hags with flowing manes, hatless and untamed.

The conical hat’s witchy debut arrived in 1693 with Cotton Mather’s The Wonders of the Invisible World, a Salem witch-trial screed. An illustration shows a broom-riding witch beside the devil, her black cone stark against the night.

Yet Kounine demurs: pointy hats were 17th-century fashion, sported by innocents like Esther Inglis in her portrait or Mrs. Salesbury in John Michael Wright’s family canvas.

No occult hex here—just high style, from steeple-like strobiloid shapes to noblewomen’s hennins, which inspired Cinderella’s and Sleeping Beauty’s pastel towers.

Why black? The hue sealed the spell. In Thomas Dekker’s 1621 The Witch of Edmonton, the devil appears as a black dog; woodcut prints demanded monochrome menace, and witches’ nocturnal sabbaths evoked shadowy evil.

Black cloaks and cones hid the hidden, amplifying dread.

The 20th century crystallized the image.

L. Frank Baum’s 1900 The Wonderful Wizard of Oz birthed the Wicked Witch of the West, her hat a pinnacle of peril.

The 1939 film’s Margaret Hamilton—green-faced, cackling—seared it into pop culture, from Bewitched’s credits to Harry Potter’s hag hordes.

Arthur Rackham’s 1907 illustrations for The Ingoldsby Legends layered gothic flair atop the sorceress’s black ensemble.

But reclamation is underway.

Feminism has flipped the script: the witch, once crone, now stands for solidarity, healing, and autonomy.

“We are the daughters of the witches you couldn’t burn” adorns merch and mantras alike.

Gregory Maguire’s 1995 Wicked humanized Elphaba as a green misfit fighting injustice, spawning the Broadway hit and films.

In Wicked: For Good, costume wizard Paul Tazewell spirals her hat earthward—reflective, organic—to mirror her grounded rebellion.

No longer sinister, it’s aspirational, echoing Charmed’s empowered sisters.

Kounine sums it: the hat’s no horror—it’s a canvas for our myths, reshaped by art, tales, and time.

Pagans see it as energy conduits; kids as candy quests. Google’s 2021 data crowned it Halloween’s top guise.

As Wicked reframes villainy, this ancient cone reminds us: symbols evolve, and so do we. What’s next— a hat for heroes?

Discover more from AMERICA NEWS WORLD

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a Reply