By Suraj Karowa /ANW ,November 28, 2025

NEW DELHI

Hospitals in Delhi have seen an influx of children complaining of breathing difficulties

— In the choking smog that blankets India’s capital each winter, no one escapes unscathed.

But for Delhi’s youngest residents, the toxic air is proving lethal, triggering a surge in respiratory illnesses and sparking parental panic across the city’s 20 million inhabitants.

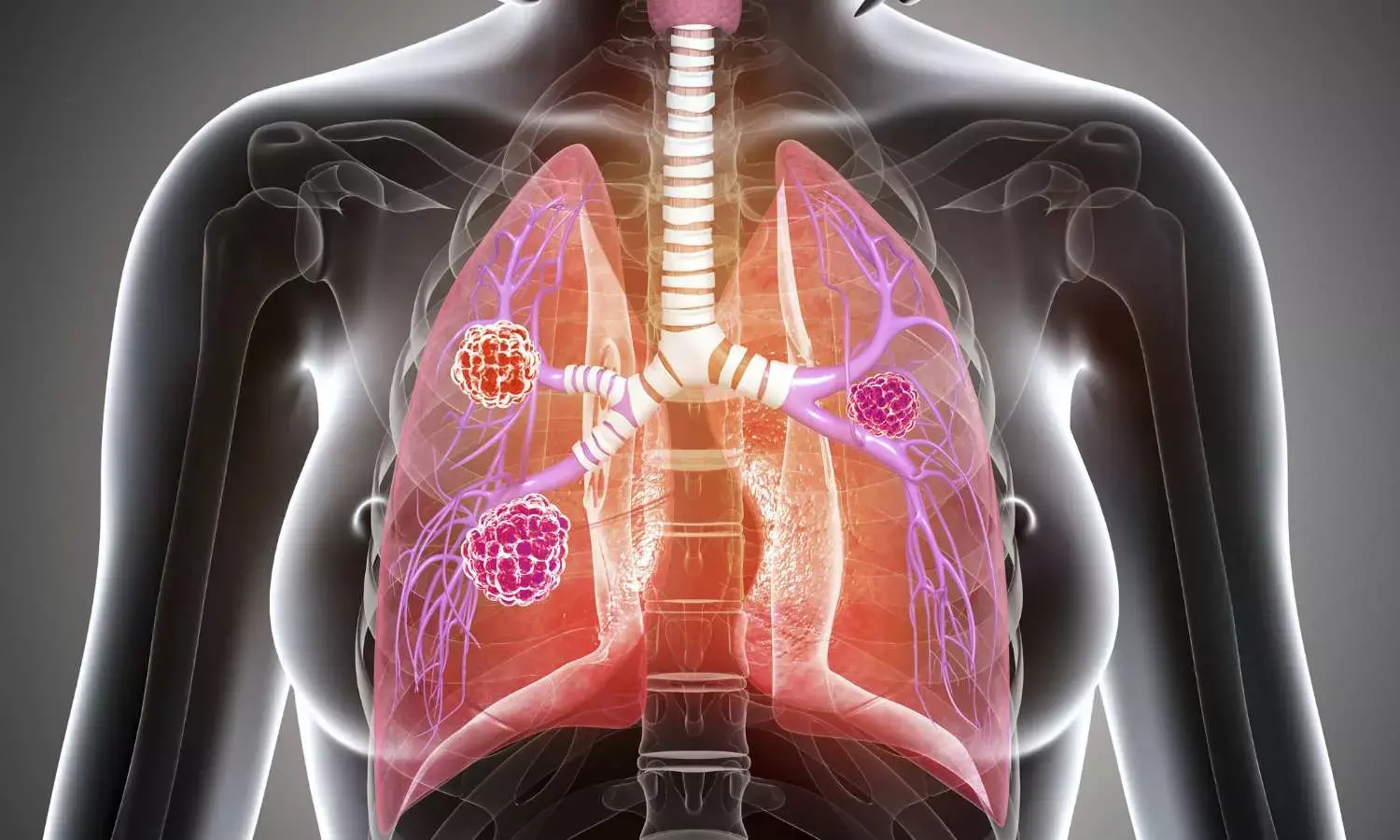

Hospitals are overwhelmed with children gasping for breath, their fragile lungs clogged by fine particulate matter that lingers like a seasonal curse.

The crisis peaked this month as Delhi’s Air Quality Index (AQI) consistently surpassed 300 — more than 20 times the World Health Organization’s safe limit of 15 for PM2.5, the microscopic pollutants that infiltrate deep into the body.

High exposure to PM2.5 – or fine particulate matter – hits children the hardest

Readings above 400, as seen in recent days, endanger even the healthiest adults, but experts warn that children, whose immune systems are still developing, face the gravest risks.

“These particles assault the child’s growing immunity,” said Dr. Shishir Bhatnagar, a pediatrician in nearby Noida, where his clinic has seen a tenfold spike in pollution-related cases.

“What was once 20-30% of my patients now jumps to 50-70% during peak smog season.”

The BBC visited Bhatnagar’s packed waiting room on a recent weekday, where anxious parents clutched toddlers mid-cough.

Symptoms emerged en masse in October, coinciding with the dip into hazardous air levels.

Women and children protest against air pollution in Delhi

Low wind speeds trap emissions from vehicles, industries, and the annual stubble-burning in neighboring states like Punjab and Haryana.

Cooler temperatures exacerbate the inversion layer, holding pollutants close to the ground.

This year’s futile attempt at cloud seeding for artificial rain underscored the desperation — and the limits — of current interventions.

Government measures, including construction halts and bans on older vehicles under Stage IV of the Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP), have become annual rituals.

Yet, they fall short. “The air is unbreathable, and our children are the canaries in this coal mine,” lamented Khushboo Bharti, 31, a mother whose one-year-old daughter, Samaira, was rushed to the emergency on November 13 with violent coughing that led to vomiting and pneumonia.

Treated with steroids and oxygen for two days, Samaira has recovered, but the trauma lingers.

“I panic every time she coughs now,” Bharti confessed, her voice trembling. “She’s bubbly, always reacting to everything — but that night, she just lay limp. It was my worst moment as a parent.”

Bharti’s story echoes countless others. Gopal, a father in a working-class neighborhood, watched helplessly as his two-year-old, Renu, developed severe chest congestion last week, landing her in a government hospital.

“Doctors say she might need inhalers long-term,” he told reporters, his eyes hollow with fear.

“What kind of damage has this air already done?” Research paints a grim picture: A University of Cambridge study analyzing data from nearly 30 million people linked early pollution exposure to stunted growth, weakened immunity, lower cognitive scores, and even heightened dementia risks later in life, including Alzheimer’s.

For Delhi’s underprivileged children — those in roadside shanties or cramped homes reliant on smoky cooking fuels — the onslaught is unrelenting.

Dr. A. Fathahudeen, a Kerala-based pulmonologist, highlighted the disparity: “Economically disadvantaged kids endure enormous lung assaults from traffic, poor ventilation, and indoor pollutants. Untreated childhood infections from this can scar lungs permanently, mimicking smoker’s chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adulthood.”

He urged affluent families to keep children indoors, hydrated, and masked with N95s outdoors — advice that filters 95% of particulates but feels like a prison sentence to many.

Schools have adapted: Primary classes shifted to hybrid mode, outdoor sports postponed.

Protests erupted on November 9, with women and children marching through the haze, placards decrying the “silent killer.”

Yet, for families like Seema’s, a single mother in east Delhi, the trade-offs are heartbreaking.

“Kids need to play, to grow strong,” she said, watching her son stare longingly out a grimy window.

“But how can I let him breathe this poison? They whine for fresh air, but we have no choice.”

The human toll extends beyond immediate illness. A recent Lancet study estimated Delhi’s pollution shaves 10 years off average life expectancy — a statistic that hits hardest at the vulnerable.

Globally, air pollution claims 7 million lives yearly, per WHO data, with India accounting for one in seven deaths.

Beijing, once synonymous with smog, has clawed back through aggressive electric vehicle mandates and coal curbs; Delhi lags, hampered by federal-state tussles and enforcement gaps.

Parents like Bharti dream of escape. “Why stay in a city where my daughter can’t breathe freely?” she asked. Her husband’s business ties them down, but relocation beckons.

“The moment we can, we’re gone.” For now, Delhi’s children huddle indoors, their laughter muffled by the haze outside.

As winter deepens, calls grow for bolder action: Stricter stubble-burning penalties, greener public transport, and international aid for clean tech.

Until then, the capital’s little ones remain collateral in a war against the skies — a war India seems perilously close to losing.

Discover more from AMERICA NEWS WORLD

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a Reply